Hwange National Park

Situated in the northwest corner of Zimbabwe on the Botswana frontier, about an hour’s car journey south of the Victoria Falls, Hwange National Park is Zimbabwe’s largest and best-known National Park. Formerly occupied by the San bushmen, the Nhanzwa, and latterly the royal hunting preserve for the Matabele king, Mzilikazi, the area was finally gazetted for wildlife conservation in 1928 and was called Wankie Game Reserve. The reserve was created simply because the land was deemed to be unsuitable for agriculture due to its poor soils and scarce water supplies. With the inclusion of neighboring Robins Game sanctuary, it was proclaimed a national park in 1930.

The Park’s area of 5,657 square miles (14,651 square km) is largely flat and lies across a watershed draining north into the Zambezi River, and southwest towards the Makgadikgadi Pan in central Botswana.

In a wetter age, when mudflats were spread across the extreme south-west of the present Park, and when swamps and forests in the north laid down the Hwange coalfields, great rivers flowed here. Today, the shallow soils north of the watershed support Mopane woodland (Colophospermum mopane), Baobab (Adansonia Digitata) in rocky places, and splendid Acacia forests along the Lukosi River. Ancient dunes, now thickly vegetated, tell of a dry period when Hwange was a sand desert. Two thirds of the park south and west of the watershed is still covered with Kalahari sand hundreds of metres deep, and here, woodlands and vleis mingle with scrub and open grasslands. In the east, better soils nourish abundant grazing and stands of Zambezi Teak (Baiklaeia Plurijuga). There are many calcrete rich areas along the watershed which are prized by the animals for the mineral salts they contain.

When the rains come, the sandveld is verdant with abundant grass and foliage, and water fills every dip and hollow. But almost all the pans and vleis become parched long before the end of the dry winter months (May- August), when drought strips the veld of its greenery. While daytime conditions are clear, warm and sunny, night-time temperatures plummet to freezing and sometimes well below.

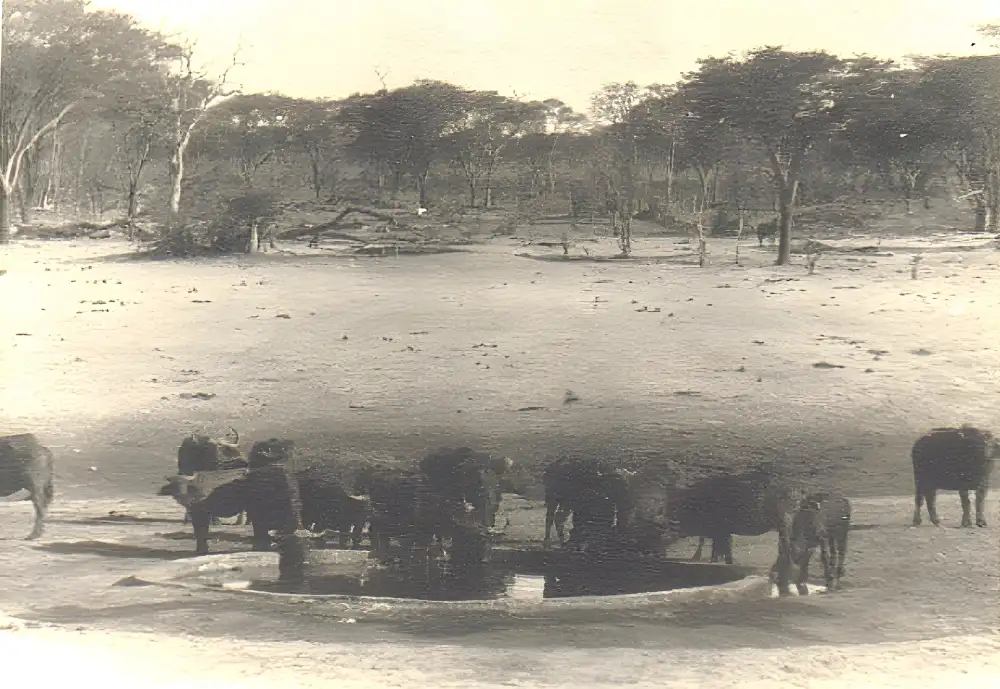

Ted Davison was the first warden of Hwange National Park and remained there for thirty years. Soon after his arrival, it became clear to him that the availability of permanent drinking water was the key to the Park’s future. Under his direction, with tireless work and dedication, boreholes were sunk, windmills erected and diesel pumps installed to create well-spaced artificial waterholes during the dry season. With water permanently available at these pans, animal numbers blossomed resulting in the impressive game concentrations we have there today.

Hwange is one of Africa’s premier National Parks, the pride of Zimbabwe’s tourism and conservation fraternity, situated in one of the world’s last remaining wilderness areas. Home to tens of thousands of elephant, large and small mammals, and an abundant wildlife, it draws game watchers from all over the world. The haunting beauty of Hwange in all its seasons and with all its inhabitants is breathtaking. HNP is one of Zimbabwe’s most valuable natural resources. The tourist industry relies heavily on wildlife as a major attraction and revenue earner and provides employment opportunities for the local communities. With an ever-increasing human population threatening encroachment into natural ecosystems, space for wild animals to exist is fast diminishing. Preserving whole ecosystems for wildlife to thrive is priceless.

However, the establishment of a contained, man-made, wildlife haven presents a serious dilemma. This conundrum was outlined succinctly by Nick Greaves in his beautiful book Hwange, Retreat of the Elephants, written in 1996 and is still a contentious topic today.

Quote:

“Only with the provision of artificial water supplies, which guaranteed reliable surface water throughout the year, did Hwange’s inhabitants manage to form stable and resident breeding populations. Concentrating animals in a fixed area, no matter how large, was inevitably going to lead to a change in habitat. In essence, this vast wilderness was created by man for the wildlife, but since it is man-made, a dilemma presents itself. Does man stand by and let the animals alter the wilderness until nature finds its own balance – no matter what the consequences – or does he step in and restore the habitat to what he thinks is a natural balance, no matter how unpopular the means may be?

This vexatious question has been debated across Africa for decades and Zimbabwe remains in the forefront of the war of words over elephant culling and ivory trading. Hwange and its elephants are at the heart of this war – and both are in the firing line.”