Hwange National Park

Situated in the northwest corner of Zimbabwe on the Botswana frontier, about an hour’s car journey south of the Victoria Falls, Hwange National Park is Zimbabwe’s largest and best known National Park. Formerly occupied by the San bushmen, the Nhanzwa, and latterly the royal hunting preserve for the Matabele king, Mzilikazi, the area was finally gazetted for wildlife conservation in 1928 and was called Wankie Game Reserve. The reserve was created simply because the land was deemed to be unsuitable for agriculture due to its poor soils and scarce water supplies. With the inclusion of neighboring Robins Game sanctuary, it was proclaimed a national park in 1930.

The Park’s area of 5,657 square miles (14,651 square km) is largely flat and lies across a watershed draining north into the Zambezi River, and south west towards the Makgadikgadi Pan in central Botswana. In a wetter age, when mudflats were spread across the extreme south-west of the present Park, and when swamps and forests in the north laid down the Hwange coalfields, great rivers flowed here. Today, the shallow soils north of the watershed support Mopane woodland (Colophospermum mopane), Baobab (Adansonia Digitata) in rocky places, and splendid Acacia forests along the Lukosi River. Ancient dunes, now thickly vegetated, tell of a dry period when Hwange was a sand desert. Two thirds of the park south and west of the watershed is still covered with Kalahari sand hundreds of metres deep, and here, woodlands and vleis mingle with scrub and open grasslands. In the east, better soils nourish abundant grazing and stands of Zambezi Teak (Baiklaeia Plurijuga). There are many calcrete rich areas along the watershed which are prized by the animals for the mineral salts they contain.

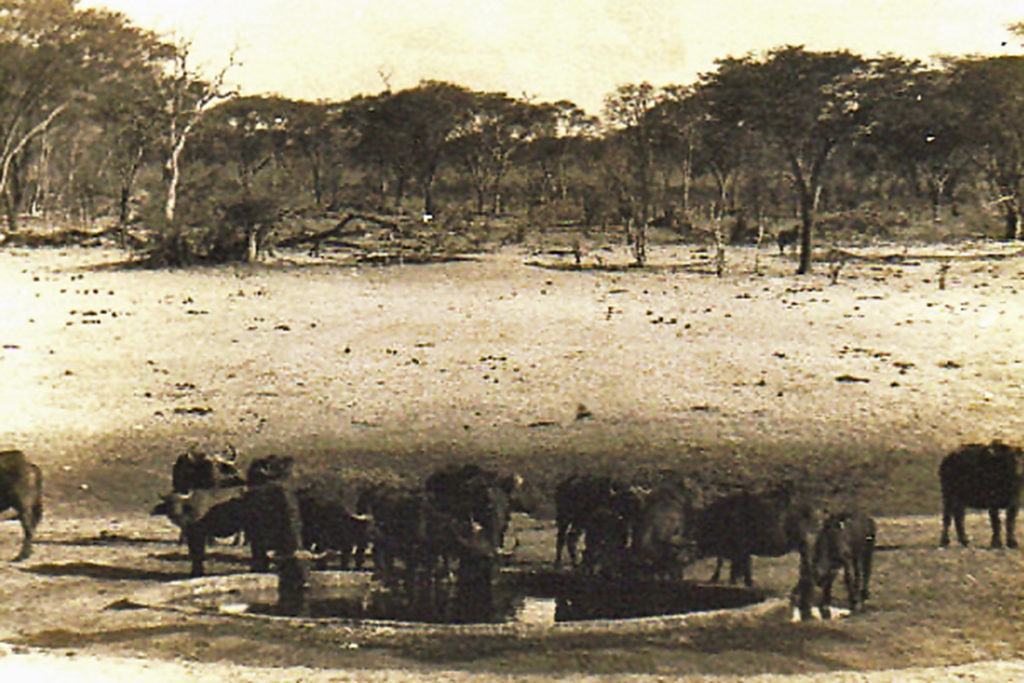

When the rains come, the sandveld is verdant with abundant grass and foliage and water fills every dip and hollow. But almost all the pans and vleis become parched long before the end of the dry winter months (April-November), when drought strips the veld of its greenery.

Ted Davison was the first warden of Hwange National Park and after a time it became clear to him that water was the key to the Park’s future. Under his direction, and that of subsequent wardens, with tireless work and dedication, boreholes were sunk, windmills erected and diesel pumps installed to create artificial waterholes during the dry season. With water permanently available at these pans, animal numbers blossomed resulting in the impressive game concentrations we have today. The responsibility lies with all of us to maintain and protect them.